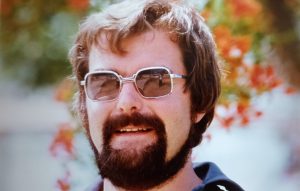

Dr Norman W. Wallace has had an interesting career in the medical field spanning several decades. He graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a degree in medicine and subsequently worked in the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of the Nazareth Hospital in 1978. Dr Wallace then trained in geriatrics and community paediatrics, which led to his appointment as a Principal in General Practice at Sighthill Health Centre in 1980. He later became the lead partner in building and establishing Whinpark Medical Centre, where he served as a senior partner until his retiral from clinical medicine in 2011. Alongside his professional work, Dr Wallace has been involved in various volunteer activities, including serving as a board member of EMMS and participating in several bike rides for the Nazareth Hospital. Dr Wallace now works as a medico-legal adviser.

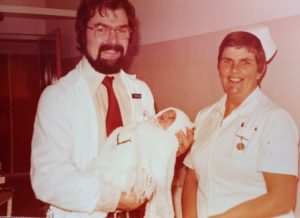

Dr Norman Wallace and Sabeen, a midwife at the Nazareth Hospital.

Yes. I’ve always wanted to be a doctor. It was somewhat strange that my mum had a picture of me reading a Jungle Doctor book aged eight. I didn’t want to be a scientist: I’ve always wanted to be a people person.

I ended up in charge of the obstetrics department, which was quite a responsibility. I didn’t have any postgraduate qualifications in obstetrics. but I was well tutored. I was able to carry out caesarean sections. I always insisted on another surgeon being in the hospital. At that time, the hospital was almost entirely run by ex-pat doctors, maybe eleven in total. We did a lot of our routine antenatal care in the town clinic near the Basilica. My time in Nazareth was recognised as training for general practice, which was very significant for me.

It’s difficult to select just one. Obviously, Hans Bernath stands out, but there were others like Fred Holmes and Philip King Lewis. I wouldn’t like to single out individuals… There was a lovely Indian lady, Shamla, who was a consultant obstetrician for the first few months I was there. I knew she was leaving, so I desperately tried to learn as much as I could from her. I think just the spirit of working together in a loving clinical and Christian environment greatly impacted me.

Yes, she’s one of the Nazareth babies. We brought her home at three weeks of age. The labour ward where my wife delivered was an eight-bedded room with no privacy. All you had was a curtain, but that doesn’t really do anything. It was quite an experience!

Vera Bramwell (midwife and tutor midwife) and Miriam Wallace holding Kevin and Catriona at the Nazareth Hospital.

© Andrew Barr Photography.

Catriona Walker and Prof Jason Leitch CBE (The Nazareth Trust’s Vice Chair of the Board) at our Holyrood event.

The experience was pivotal in terms of my medical and spiritual development. It was a tremendous opportunity to develop my clinical skills and learn from experienced practitioners. It also gave me a huge medical perspective and quite a lot of confidence in dealing with demanding clinical situations. I would have been doing far more menial routine tasks in the UK, but in Nazareth, you were dealing with the patient’s needs. I still look back to my time there. It taught me collaborative working: I’ve never been the type of doctor to say, “I know everything”. I’ll always try to take advice from anybody. The midwives, particularly the local ones, were very experienced. I also admired Hans Bernath, who was such an experienced clinician.

Working in a Christian caring environment allowed me to develop some spiritual maturity. Living in a community like that was challenging, facing inevitable pressures because you’re living in an almost claustrophobic compound, just down from what is now known as the Doctor’s House.

I did bike rides in 1994, 1996 and 1998. In between, we had a family holiday there, and I also took a church group in 1997but I have not been back since the last bike ride in 1998.

They were multinational. There were quite a lot of Americans, some Swiss and some Dutch. We did different routes, basically around the north of Israel. We also went into Jordan, Petra and then down to Aqaba. The weather was mainly good, but we had one or two days of rain. It’s the wind that’s the problem. Pedalling against the wind is hard work! Once, on the East Bank of the Jordan, whilst we were eating, we had flies descending on the food, so you had to blow them off. We then realised they were using sewage water from the villages to irrigate the fields. That’s why the flies were there, and within hours people were quite ill with diarrhoea and vomiting, which is not what you want on a bicycle! Luckily, I was fine.

I walked the Camino de Santiago a couple of years ago: the Camino Ingles, starting from Ferrol, which was 100 miles. Many English people in the past centuries did that, but it’s not too demanding. It’s a beautiful country! When you arrive at the cathedral, some people can hardly walk because their feet were so sore with the blisters, but everyone is quite euphoric, just as in the bike ride, because you’ve done it and get that adrenaline rush.

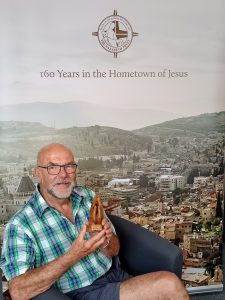

I brought one of my wee mementoes. When you finished the bike ride, you always got something: this was the memento from 1998- praying hands.

Dr Wallace holding a gift from the 1998 bike ride at the Nazareth Trust’s Edinburgh office.

Yes, it is. You see olive wood everywhere. The bike rides provided a wonderful opportunity for camaraderie and fellowship. I think it was 1998 when I got to know John Vartan. He was the great-grandson of Dr Vartan, who founded the hospital. That was so special. We’ve had quite a lot of reunions here in Scotland in, for example, Aviemore and North Berwick.

I’ve always wanted to try and give back to the Nazareth Hospital when I can, which is why I did the bike rides and served on the Board a while ago. I owe so much of my spiritual and medical development to the hospital, and many people resonate with that. I’ve never heard anybody who has had significant involvement in the hospital who hasn’t been very positive about the experience, which is quite unique, particularly in a healthcare setting. Here people talk about the difficulties of the NHS, and of course, there are difficulties, but in Nazareth, there were some months when we didn’t even know if we would get paid. My cousin Eleanor Walker was working at the hospital as an anaesthetist. Her father, Arnold Walker, generously supported us and also provided us with a car. We ordered a nice little Peugeot from France because cars in Israel were very expensive. It travelled from Marseille to Haifa, and Fawzi, one of the admin hospital staff, went with me to customs to pick up the car.

It’s a huge international port. Fawzi helped me with all the admin paperwork. It was all done in Hebrew, which of course, was as bad as Arabic as far as I was concerned. We drove through this huge port, and there was the car, sitting at the end of the pier, completely covered in a thick gooey wax. Apparently, they coat the cars to protect them from seawater. When we got there, there was nothing: no windscreen wipers, no wing mirrors, no hubcaps… Fawzi said: “Oh no, the car has been vandalised!”. But we had the keys, so after opening the boot, we found all the things that were missing. They had taken them all off so they wouldn’t get damaged in transit. Back in Nazareth, I asked Salim, the hospital pharmacist, if he had any solvent to get the wax off the car. He said: “I’ll see what I can do”. In a couple of hours, he said: “Dr Wallace, would you like to come and see your car?” There was this gleaming car which almost brought a tear to my eye. It was in showroom condition. Absolutely immaculate!

He took some solvents from the pharmacy and asked some of the workers in the compound to clean and polish the car. It was beautiful! I couldn’t believe it. When we went back home, we left the car at the hospital for the staff to use, and it ran for quite a number of years, I believe. It was so nice to be able to jump in your car and explore. These are great memories.

Dr Norman Wallace in Nazareth.

I didn’t have a specific role; I was just a general board member, other than developing the Hawthornbrae Trust, which was a benevolent Trust that helped convalescents. I hope it’s still running. Robin Arnott was on the board at the same time as me. It was an interesting and difficult time because we were beginning the separation of the Nazareth Trust from the general work of the EMMS. We had to make a lot of difficult decisions, many of which we couldn’t fully understand because there was so much legal complexity.

You’re best to describe it as a forensic medical examiner. I was a police surgeon from 1987 to 1996. It’s a bit of a misnomer. You’re not a policeman, and you’re not a surgeon either. You’re involved in things like child abuse and rape: examining the victims, doing forensic tests, and presenting them in court for cross-examination. I enjoyed it, but it was very stressful because a lot of these sad cases were out-of-hours.

No, it’s not NHS. You’re employed by the Crown Office. I have been clinically retired from practice since 2011 but still work as a medicolegal adviser. These are all civic cases, mainly alleged GP negligence. I write reports and occasionally appear in court.